Voices of Resistance in the Medium of Silence A first look at graffiti in the former Stasi remand prison, Berlin-Hohenschönhausen

Picture an early MTV video closing in on the only customer in an empty restaurant, a young man sporting a mane of shoulder-length blond hair with fringe. His expression is sinister, and as the camera nears him he opens his mouth; the camera dives in – not down his throat – but down an endless institutional hallway. The video cuts to a scenario where his bandmates are cramming him into a concrete box. In subsequent nature scenes they appear together, manhandling their V-model electric guitars and in a few cuts they do this while high-kicking a cement wall topped with hoops of razor-wire. The video returns to the nightmare trip through the hallway at the chorus of »I Want Out«.

Counting lines and »Helloween«. Cell 326 Berlin-Hohenschönhausen

One of the issues with inscribed graffiti, perhaps with graffiti in general, is that a viewer must outwit the mind’s tendency to see what it wants to see. In prison cell 326, the word »Helloween« appears at first to read »Halloween«; scratched in the downward-facing slope typical of a right-hander writing at eye level. However exchanging an »a« for an »e« is the difference between a holiday – and a groundbreaking power metal band from Hamburg. In 1988 Helloween promoted the hit single, »I Want Out« on that music video and later included it on the popular album »Keeper of the Seven Keys II«.[1] This song would be a real earworm for someone incarcerated where the graffito appeared, Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. So, too, the video’s imagery of the straight, empty hallway, which overlaps significantly with reality. On the wall near the »Helloween« graffito and underneath some badly done whitewash, »Metallica« appears by a different hand. Even though the graffiti are anonymous, music let this researcher know the mindset, or at least the mental soundtrack, of an inmate in cell 326 sometime in, or after 1988.

The following is a report on original research and documentation of graffiti conducted in 2017-2022 at the former central Stasi remand prison, now the Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen.[2] It is the first exposure of these graffiti from the last years of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).[3] In the research, the oldest graffiti found in the cells date from around 1987 and the latest from early 1990. Later it will become clear that these markings are in a precarious state of preservation. Fragile and vulnerable, they are valuable hints of individuality inside a system designed to force conformity. Berlin-Hohenschönhausen was the central remand prison of the Ministry of State Security (MfS) operated by the state security forces (the Stasi) that supported and guaranteed the power of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) regime.[4] It was the largest of seventeen remand prisons distributed throughout East Germany. Although the treatment of inmates varied greatly case by case and over time, many prisoners endured intensive and often random interrogations, deprivation of privacy, extreme loneliness and psychological torture. Physical violence was not officially condoned in the later decades. As most prisoners were accused of political crimes, interrogators manipulated the latter conditions to coax either self-incrimination or a confession from their subjects before they were brought to criminal court and sentenced.

Graffiti in this context demand different considerations from graffiti elsewhere, including in other prisons. This fact is touched on lightly here, but detailed in my doctoral thesis, »Intentions Through Hands and Time« (working title, expected in 2024). Methodological and theoretical models will also be missing from this report, but they can be found in my thesis as well as in »An Autopsy of Plain Lines: Examples from the former Stasi prison, Berlin-Hohenschönhausen« (book chapter forthcoming 2024). This report puts the content of selected graffiti in the foreground along with counter cultural and social considerations from the 1980s that they bring to light; in the background we have the present-day institution that houses the graffiti, the Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen (HSH). The prison’s history is deep with violence, repression, grim architecture and political machinations – but this report is about what is on the surface – and the hints that graffiti leave about the cultures and attitudes among some of the most recent detainees.

Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, 1989 and background

With Soviet influence in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Berlin-Hohenschönhausen was associated with brutal interrogation techniques aimed at breaking down resistance to the nascent communist dictatorship. By 1961 when the Berlin Wall surrounded west Berlin, the focus had turned to dismantling opponents of the regime using psychological techniques both inside and outside the prison. Some of the prison’s most recognised inmates from this period were prominent dissidents and civil rights leaders like Jurgen Füchs who was at HSH in 1976-77; Ulriche Poppe, there in 1983-84; Barbel Böhley 1983-84 and 1988; Freya Klier, 1988. Cultural activists and musicians were imprisoned, most notably Christian Kunert, 1976-77; Jürgen Pannach, 1976-77 and Stephan Krawczyk 1988.[5] These visible and articulate former inmates were among more than 10,000 people held in this prison complex between April 1951 and January 1990. Still, despite the prison becoming a Gedenkstätte and the establishment of a Contemporary Witness Archive with more than 150 contributions, the greatest number of former inmates are silent and this is especially the case for inmates from the prison’s last days.

Prison walls and watchtowers are typically visual cues for citizens about law and order in society: they are powerful either because the prison is central (La Bastille) or more currently powerful in the popular imagination of remoteness (Alcatraz, ADX Colorado USA).[6] Hohenschönhausen, by contrast, was invisible. As the ideal carceral architecture for a regime of secrets, it lay in a restricted zone in a suburb of Berlin which, by 1972 was a blank area on civilian maps. Wardens and others who went to work within lived, for the most part, in the surrounding neighborhoods. Windowless delivery vehicles brought the captives, who were often blindfolded. Vans were labeled with things like »Back Kombinat« or »Frischer Fisch auf den Tisch« – sometimes the means of delivery were hearses, or laundry trucks[7].[8] To the disoriented prisoner, the prison cell could be anywhere in Berlin, and thus everywhere; and, similarly, for the SED the practical differences between criminals and citizens were also blurry.[9] Even after the fall of the Berlin Wall and while the rest of East Germany’s power structures were unraveling, the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison complex remained somewhat of a secret.[10] During the winter of 1989-90 as citizens stormed other government buildings the prison stayed occupied and heavily guarded. It held inmates through the general amnesties of December 1989; even as the MfS headquarters were dismantled in January 1990 it did not officially cease operations. The prison simply fell into disuse.[11] By February 1990 it was a remand prison once again, this time for so-called normal prisoners. Between November 1989 and January 1990 the Stasi removed traces of anything that »contradicted international legal norms«,[12] including inmate records.[13] They did not get all of the graffiti.

Encircled »A«, whitewashed and scratched out. Cell 331 Berlin-Hohenschönhausen[14]

The Gedenkstätte: Site History and Collection

The ground of Hohenschönhausen seems to have seeded subordination that repeated and magnified with successive generations. It began late in the 19th century when manufacturers turned subdivisions of a large farming estate, Hohenschönhausen, into an expansive industrial area of factories and worker housing. An equipment manufacturer who produced meat processing machines owned the specific parcel that later became the MfS complex including the prison. In 1938, the National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization acquired that plot along with its facilities, repurposing some of them and building a modern industrial-scale kitchen to supply Berlin’s armament factory workers.[15] In surrounding areas they built barracks that held prisoners of war and laborers who were forced to work in the factories. It became a military zone. When the occupying Soviet forces acquired the plot and its operations, they converted the basement of the industrial kitchen into a dungeon-like prison for captives of the Stalinist East German regime. By 1951 the Soviets gave control of the prison to the Stasi who continued to use it heavily through 1960. Then, as the focus of detention shifted from anti-Communist to mass civilian arrests, the Stasi came to need a larger central remand prison. Berlin Hohenschönhausen, a state-of-the-art design in 1960, was built by forced labor from the prison.[16] For almost a century the Hohenschönhausen suburb of Berlin featured social subordination, either of factory workers, soldiers or prisoners. It is a place where one Foucaultian structure slid into the next, as Suzanne Buckley-Zistel[17] has related, with the architecture and methods for managing people handed down step-by-step from the past. This seemingly autochthonous system of domination, then, is what I would like to examine through the graffiti that so gently present themselves in whitewash. Are there alternative forms of resistance in these enunciations, scratched into the medium of silencing?

The prison became a Gedenkstätte in 2001 after more than a decade of petitions from former inmates and citizens’ groups. It is both a memorial to those who suffered there and a museum with guided tours to educate present and future generations about the past. Problematically, there were at least two prisoner groups vying for commemoration. Already in 1988, victims of Stalinist persecution were demanding commemoration on prison grounds, even while other political prisoners were inside enduring Stasi tactics at the same time.[18] Carole Rudnick[19] deals with the machinations of the Gedenkstätte’s beginnings in detail, including the various ways these groups defined themselves as victims of the State. While the overarching concern at the Gedenkstätte is now for human rights and social justice, it may be understood as the latest in the succession of institutions to manage thousands of human experiences on that ground. Its stated purpose is »commemorating the injustice committed in this place«,[20] which it does through the selective display of artifacts and staged histories, archiving, caring for Contemporary Witness testimony and promoting tours guided by former inmates.

Graffiti In A Commemorative Context

It is perhaps telling that the collection does not include graffiti per se. This raises questions not only about where it might fit into the institution but more importantly: what kinds of voices are left out as a result. This is not entirely a question of recognition. A large part of the problem lies with the material itself. Compared to other German prisons that feature graffiti – Köln’s El-De Haus from the National Socialist period[21], or especially the Soviet remand prison in Leistikowstraße[22] or the former prison Gedenkstätte Lindenstraße in Potsdam that spanned several regimes[23] – the graffiti at Berlin-Hohenschönhausen are less spectacular. Among many possible reasons why HSH did not take an interest in their graffiti the way the latter institutions have, two will be considered here. First, the uniquely repressive conditions at HSH produced graffiti that are difficult to see (and photograph), made in haste, spare, perhaps banal – and mostly anonymous. As a consequence, and this is the second reason, they might not seem to provide much substance for traditional scholars. In the words of a former director, since they »already know« who was in these cells, what is the point of looking at this graffiti?[24] Given the importance of his suspicion about their authenticity and relevance, I have been exploring the value of anonymous or un-famous voices. I will argue here that if graffiti may be understood as unofficial witnesses, then they seem to offer something different from official Contemporary Witness testimony. Among other things, patterns of material attributes and locations of graffiti offer alternative ways to understand the experience of repression and incessant monitoring. More specifically, variations in these patterns are of interest because they give insight into individual, non-conformist responses to authority – as does the content of graffiti. This is a much larger topic than space permits, so the following is an overview and for the likely questions it may provoke I would refer the reader to my forthcoming texts already mentioned.

Right now, the graffiti are in a precarious state of preservation. The 1960 building featured three floors of prison cells, of which the first and second floors have been renovated. The third, where the graffiti under study are found, is closed to unaccompanied visitors. The second floor also had prison-era graffiti but tour groups added writing to the walls and this created a perception of contamination, reflected in the former director’s suspicions. In fact, suspicion about authenticity is a consistent problem, not only for graffiti studies in general, but especially in the institution’s context of forensic historical fact-finding. For this reason, the second floor was renovated in 2019 without preserving wall inscriptions. I argue elsewhere that the location, manner and content of graffiti made under repressive conditions are entirely different from later graffiti, particularly tourists.[25] Contemporary visitors typically aim for high visibility and they write their names front-and-center, with confident strokes; most prisoners did none of this – as the material from the third floor demonstrates. Sensitivity to the warden’s gaze and how it shaped choices, even about where to write graffiti, would have made an interesting educational point. This is especially clear when mapped.[26] On the third floor, twelve of the cells had a thorough whitewashing in late 1989, which explains the near total absence of graffiti there. In 2022 the cells on the third floor were selected for bulk storage, including the cells with the remaining GDR-period graffiti, the subject of this report. Graffiti in whitewash are fragile enough to be erased by most kinds of contact, so the fact that they are now in a storage area may expose them to less traffic. It may also open them to different kinds of damage. In 2022 the Gedenkstätte kindly hired photographer Dirk Vogel to accompany me to document the graffiti as well as possible in these circumstances and many of the photos in this report are his.

The Graffiti: Content, Location and Population

In this extreme context, all scratching is meaningful. Two strokes in cell 310. Berlin-Hohenschönhausen

There are over 300 markings in twenty-one of the thirty-three cells on the third floor. Eight of these are group cells suitable for three or more inmates, twelve were for one or two people and one was for one person – although these numbers would have varied based on the overall population and the administration’s wishes. All the cells have uniform glass block windows and thin vents for outside air. Every cell door is fitted with a circular spy-hole; group cells have an additional, rectangular panoramic spyhole. Wardens checked on inmates twenty-four hours a day, sometimes up to once every two minutes, and so most of the graffiti concentrate in the blind-spots, in areas less visible from the spy-hole. Many seem hastily, lightly and finely incised, probably cut into the powdery whitewash with a fingernail or a utensil. Notable exceptions to these material observations will be discussed later.

Before going further it is necessary to explain that what constitutes »a graffito« in such a repressive context is broadly defined.[27] My general approach is to include as many kinds of markings as possible because damaging the walls was an explicit violation of the rules: any incision is transgressive regardless of its legibility and content.[28] Making just one scratch could be understood as intentional or even existential – and only some prisoners did this. Many did not have this impetus, or they were worn down by interrogation, they did not dare, or what they wrote was covered over in whitewash. Many voices, in other words, are still silent. Most, but not all of what do come through to the present are anonymous. There are fifteen instances of initials and twenty-one names, of which eight correlate with prison records. Some, for example »NENA« in cell 306, may refer to others – in this case, Nena is probably the Nena of »99 Luftballons« atomic rock fame.

Opposition figures from the 1980s who articulated their dissent through sincerity and organized resistance are the inmates featured on the HSH website. Another attitude comes through in some of the graffiti from the ‘80s: the apathy and defiance of Punks and Anarchists. As punk musician Henryk Gericke put it, while the Opposition negotiated with the government, the Punk approach was to have no political conviction at all, which was »something very liberating in the GDR«.[29] In this sense a large, confidently made graffito located in the warden’s view can reveal a certain counter cultural mindset about authority. While I have suggested that any kind of scratching the walls is a gesture of resistance, this is another strategy: to be defiantly within the warden’s gaze. One unique example is cell 307, with large »Freedom for Skinheads« and »Skinheads Forever« scraped lightly around the door; 30 cm high cartoon hands making the peace sign on the side walls, a small encircled »A« by the door and »Ausgang« written over the door that would have blocked the spyhole while being drawn.[30] This graffiti is by far more expressive than most in the study. More often there is demonstrative apathy, or a risking of additional punishment only to write something banal or funny: this is another kind of opposition. Take, for example, the carefully written »body-building« [sic] below. The graffito is in a corner by a cabinet, a typical place not directly in the warden’s line of vision and the deliberate cursive lettering, with the curled up »y« and »g«, implying no haste. The writing goes along above a line of counting marks often associated with days spent inside. The humor is in the juxtaposition of the two: what might be tallied, pushups? Risk is in the implied fitness regimen because exercise was an extreme breach of inmate protocol – and the official GDR opinion on bodybuilding was to condemn it as narcissism. It was rehabilitated by the late 1980s but only as »Kraftsport«, not the purely western »bodybuilding«.[31]

»Body-building« [sic.] Cell 311 Berlin Hohenschönhausen

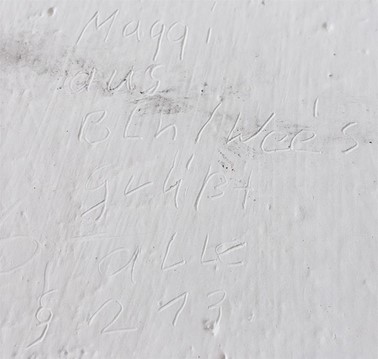

In another cell, a rather humorous graffito calls out greetings to west Berliners, from Maggi who identifies herself with §213, the very common charge of trying to escape the GDR.[32] It is also carefully written, especially the section symbol »§« and it is found in another typical hiding place, on the far side of the cell’s cabinet. Section numbers 213, 219, 211 and more can be found in many places, but it was the specificity of this claim that suggested the authenticity of this graffito, and it triggered some interest among the administration for the graffiti on the third floor. Three essential things are happening in it: a personal identification with a section of the GDR law code; the non-central location of the marking that is visible but out of the warden’s line of sight; and an ironic greeting to west Berliners.

»Maggi aus BLn / Wee’s grüßt aLLe §213« [sic] cell 308. Berlin Hohenschönhausen

Ottifant, a drawing in dust seen from an angle. Cell 330. Berlin Hohenschönhausen

By the mid-1980s most East Germans were able to pick up television stations from the West: all except the population of Dresden which, for this reason, was called »the valley of the clueless«. Antennas explain why elements of western culture appear among the graffiti, like an MTV logo and the cartoon character Ottifant drawn large (47 x 38 cm), riding his bike through a minimal but sprawling landscape. This graffito was first among several ‘dust drawings’ I discovered. The initial surprise of seeing Ottifant in a particular cast of natural afternoon light was only superseded by seeing how it was made, because it is above standing eye-level, above the regular whitewashing and other incised graffiti. It seems that a left-handed inmate stood in the right-side windowsill of a group cell, and reached with cloth or perhaps toilet paper into the central wall and drew in the grime accumulated up high (dust, cigarette smoke stains). The maker held onto a hole in the air vent with their right hand while reaching. »HOLT MICH HIER« is written next to this hole; later, someone added »RAUS«. These graffiti build an overall comic picture, not just of Ottifant but also of the inmates’ antics and, with the final addition of »raus« notwithstanding, a sense of insouciance about the guards’ oversight. The wardens were not unaware of all this activity. On their side of the door, there is a piece of adhesive tape mounted below the spyhole with the penned words, »Fernsehn raum« [sic.]

Although they did their best to suppress western influences, by the late 1980s the East German authorities considered extending cable access to Dresden housing developments: just to present the appearance of fair access to desirable t.v. programs.[33] The East’s broken grip on western influence shows in the graffiti, most notably in the dust drawings, but also through inscriptions of western music groups like Helloween, Metallica and The Cure. Punks, Goths, metalheads and the like were mostly from younger generations and their demonstrative tastes and attitudes not only attracted suspicion (often intentional) but also keen MfS oversight and targeted arrests. Words from the GDR’s Opposition anthems of the immensely influential Wolf Biermann do not appear.[34]

One strangely eastern feature of all this graffiti is the prevalence of the piča, or the pointed symbol of a vulva. In most graffiti there is a predominance of phallic imagery and although it might vary in style, I venture to say that it is nearly universally common. Not so for Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. There is not one phallic symbol among over three hundred graffiti, and only one textual reference to masturbation. In a summary of victim reports one former inmate imprisoned in 1987 said that masturbation was not uncommon even with the constant police monitoring.[35] For him, however, the conditions were a debilitating and painful »deprivation of private life«; he had different things on his mind than sexual desire. Other prisoners must have had similar responses to his but even so, the phallic symbol is not necessarily a sexual reference. It can be derogatory. The same applies to the piča. This diamond shape with a bisecting line is found next to »SED« (cell 305), below »OSTEN« (cell 309); and in five other places it stands on its own. Unlike two other, more detailed and cartoonish pictures of the same female anatomy which seem aspirational (cells 307, 329), the piča symbol has variable profane meanings: »F*ck the SED«, »F*ck the East« or something like »The East is a bitch«. Interestingly, its use is most often associated with the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, where it can be regarded as highly offensive. Hungary was one of the border countries to which East Germans fled, and were often arrested at this time.

»oSTEN« and vulva (F*ck the East), cell 309. Berlin Hohenschönhausen

Conclusion

Many Germans from both East and West were unaware of the size and effects of changes happening during the months of the Peaceful Revolution. Prisoners even more so: the world where they were arrested, the world they were isolated from, was rapidly transforming. People imprisoned in 1989 were apprehended and incarcerated under circumstances that reflected the failing, decaying communist dictatorship. They were released into quite different circumstances: a society exploring new freedoms and tilting toward reunification in 1990. Former inmates have different and changing ways of coping with their prison experiences – many have buried them – and in some ways society buried them also, distracted by the freedoms and different opportunities that came along with the Peaceful Revolution. Outwardly, the goal was achieved. Inwardly there were still, are still, people overwhelmed by the personal costs of this freedom[36]. Because the operations at Hohenschönhausen did not officially shut down when the MfS was dissolved, some of the last inmates faced continued deception about amnesty. One former inmate told me that when he was released in late 1989 it took him time to realize that there were no longer two distinct countries; that he had won a futile amnesty and he questioned the value of his long-awaited train ticket to the West.[37] Inmates from 1987–1989 are relatively silent now but their graffiti show how they had been vocal, idealistic, rebellious, and it shows their interests and things that some of them believed in enough to risk writing on the walls.[38] Above all, there were hints of humor in the face of profound unreason. Looking at it this way, the mass of all the markings on the walls represents a varied crowd of resistance: a Selbstbehauptung (self-determination) that is somewhat incongruous with the victim-perpetrator narrative often used in the telling of GDR history. In this sense these graffiti are an essential part of the ongoing project of parsing what happened at the prison and to newly freed prisoners during the excitement of the changes taking place in Germany. The window of time that their graffiti represent is a special testament to the way the GDR was toward its very end: while Contemporary Witnesses contribute their personal experiences through the lens of memory, graffiti present collective, anonymous views from a particular moment. These narratives stabilize each other and they are both necessary for better understanding the past.

The author would like to thank the Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen: the director Dr. Helge Heidemeyer for access to the prison cells while conducting this research, Dr. Elke Stadelmann-Wenz for her support and critical review, and André Kockisch for his early interest.

[In the print issue of Indes 4/2023 this article was translated to German, by request of the author the original text is published here.]

[1] Kai Hansen & Helloween, »I Want Out« (music video), 14.08.2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FjV8SHjHvHk.[2] The initiative to study graffiti at HSH came from outside the institution. During a year-long international artist residency in Berlin, I visited the prison to look at their records of modern inscriptions. Because of my empirical approach I was taken to the area on the third floor where I noticed an abundance of graffiti not in the records (see fn. 3). Afterward I proposed an in-depth survey-recording of all the markings on the third floor, which led to my PhD thesis work.

[3] Some graffiti were in a 2006 internal report by the restoration team Boerger and Boerger in collaboration with the State Criminal Police Office’s Competence Center of Forensic Science (Landeskriminalamt Kompetenzzentrum Kriminaltechnik). It covers selected graffiti in cells, the wardens’ markings in corridors and site conditions.

[4] Stasi motto was »Der Schild und Schwert der Partei«, the shield and sword of the SED.

[5] Ulrike Lippe, Prison Biographies, https://www.stiftung-hsh.de/history/stasi-prison/biographies/.

[6] This relationship between the architecture of incarceration and its effects on society and inmates is detailed in a variety of essays collected by Elizabeth Fransson et al. (Elizabeth Fransson et al., Prison, Architecture and Humans, Oslo 2018).

[7] Vgl. Elizabeth Martin, »Ich habe mich nur an das geltende Recht gehalten«: Herkunft, Arbeitsweise und Mentalität der Wärter und Vernehmer der Stasi – Untersuchungshaftanstalt Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, Baden-Baden 2014, p. 168.

[8] From an official standpoint the factuality of these anecdotes might be challenged, but they are quoted from Contemporary Witness interviews conducted at HSH (1996, 1999, 2001, 2007) and held in the HSH Contemporary Witness archive (Martin 2014, p. 168, fn 592–595).

[9] Vgl. Jens Gieseke & David Burnett, The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police, 1945–1990, New York 2014, pp. 48–76.

[10] John Schofield and Wayne Cocroft have a good map of the prison in 1989, showing it within an expansive, restricted access Stasi complex of technical facilities. (John Schofield & Wayne Cocroft, Hohenschönhausen: Visual and Material Representations of a Cold War Prison Landscape, New York 2011, p. 247).

[11] Vgl. Carola S. Rudnick, Die andere Hälfte der Erinnerung: Die DDR in der Deutschen Geschichtspolitik nach 1989, Bielefeld 2014 p. 231.

[12] Rudnick, p. 233, citing Krause, Werner H.: »Ein Wiedersehen am Ort des Leidens«, in: Berliner Morgenpost vom 15.09.1994. »Unmittelbar nach der Wende veranlasste die Modrow-Regierung, all dies in der Haftanstalt zu beseitigen, was internationalen Rechtsnormen widersprach. [...] Es ging ihr [der Regierung] dabei ausschließlich darum, belastende Spuren zu beseitigen.«

[13] Destruction of prison records make it difficult to know whether the Stasi documented graffiti. For her research Julia Spohr has referred to the complete register of prisoners at Hohenschönhausen in documentation from the Prison Department. Vgl. Julia Spohr, In Haft bei der Staatssicherheit: das Untersuchungsgefängnis Berlin-Hohenschönhausen 1951–1989, Göttingen 2015, p. 23.

[14] Typically an »anarcho-A«, it has been suggested that in the GDR this symbol also indicated »exit«. Here, because of its location (not over the door) this was probably perceived as the anarcho-A, especially since it invited scratching out. This content and context re-emerges later in the essay.

[15] The National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization (Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt) was an organization of the NSDAP.

[16] Vgl. Peter Erler & Hubertus Knabe, Der verbotene Stadtteil: Stasi-Sperrbezirk Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, Berlin 2014. I am indebted to Dr. Elke Stadelmann-Wenz, Leitung Forschung at HSH for her clarifications and additions reflected in the site history.

[17] Vgl. Suzanne Buckley-Zistel, Detained in the Memorial Hohenschönhausen: Heterotopias, Narratives and Transitions from the Stasi Past in Germany, Cambridge 2014.

[18] Vgl. Rudnick, p 227.

[19] Vgl. Rudnick 2014.

[20] Vgl. Ulrike Lippe, Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, https://www.stiftung-hsh.de.

[21] Vgl. Werner Jung, Wände, die sprechen, Köln 2013.

[22] Vgl. Ines Reich & Maria Schultz, Sprechende Wände, Häftlingsinschriften im Gefängnis Leistikowstraße Potsdam, Berlin 2015.

[23] Vgl. Sebastian Stude, Namen in der Wand, Potsdam 2020.

[24] Author’s meeting with prison administration, Spring 2018.

[25] »Intentions Through Hands and Time« (working title) PhD thesis, expected 2024.

[26] »Intentions Through Hands and Time« (working title) PhD thesis, expected 2024.

[27] I explore this in detail elsewhere, »Intentions Through Hands and Time« (working title) PhD thesis and »An Autopsy of Plain Lines: Examples from the former Stasi prison Berlin-Hohenschönhausen«, both expected in 2024.

[28] The Wardens’ manual for house rules, sections 1.3 and 1.4 include rules about graffiti: The cell walls, furnishings, sanitary facilities… may not be defaced, soiled, damaged or destroyed. No markings of any kind can be made without permission, including underlining distributed press and literature. For infractions, four tiers of disciplinary action are available to the warden, ranging from expression of disapproval to 14 days of »arrest«. Abt. XIV BstU 000380 BdL / 35 / 1986.

[29] Vgl. Henryk Gericke »Too Much Future!«, in: UNEARTHING THE MUSIC (Blog), 14.05.2019, https://unearthingthemusic.eu/posts/too-much-future-henryk-gericke/. Gericke was not at Hohenschönhausen.

[30] See fn 14. Here the encircled »A« is consistent with the other graffiti in the cell, while »exit« is fully written out over the door.

[31] Vgl. John M. Hoberman, The Transformation of East German Sport, Champagne 1990, p. 67.

[32] Gieseke & Burnett 2014 (especially p. 137) detail the GDR Law Code and the sections most commonly used, and contorted for use in the late 1980s.

[33] Vgl. Gieseke & Burnett 2014 p. 136.

[34] Although singing one of his songs caused an extended stay without outdoor exercise for one inmate in 1989, see fn. 37.

[35] Vgl. Christina Lazai et al., Das zentrale Untersuchungsgefängnis des kommunistischen Staatssicherheitsdienstes in Deutschland im Spiegel von Opferberichten: Die Haftbedingungen in der Untersuchungshaftanstalt Berlin-Hohenschönhausen 1947-1989, Berlin 2009, pp 21-22.

[36] Vgl. Buckley-Zistel 2014 pp. 113-115.

[37] From a personal conversation with Harro Hübner, incarcerated five months in cell 326, late 1989 (May 2022).

[38] From 2022 to early 2023 the Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen hosted a call on social media for Contemporary Witnesses from the late 1980s, willing to discuss their memory of graffiti in prison. It elicited only two responses.

Quelle: INDES. Zeitschrift für Politik und Gesellschaft, H.4-2023 | © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen, 2024